Understanding Compartment Syndrome and Your Rights

Serious lower-extremity cases are rarely about medicine alone. They are stories of survival, adaptation, and the permanent shift in how a person moves through the world. For trial lawyers, the challenge is translating that story into evidence that meets the statutory thresholds for recovery and persuades a jury to value the full human loss.

This guide was built for that purpose. It is meant to sit in a trial notebook, not on a bookshelf. Each section connects the medical facts of a right-leg injury to the legal arguments that control compensation in New York and New Jersey. The focus is practical—how to introduce photographs, question surgeons, prepare experts, and argue damages without losing juror attention.

Catastrophic leg injuries appear in many forms: a motor-vehicle rollover, a fall from scaffolding, an industrial crush between a forklift and loading dock, or a pedestrian struck by a delivery truck. However they start, they end in the same sequence of surgeries, hardware, infections, and—sometimes—amputation. Understanding that progression helps you tell a credible, linear story in court.

Trial Hypothetical:

A construction worker is pinned between two steel beams. He arrives at the trauma bay with an open tibia-fibula fracture, pulseless foot, and heavy contamination from concrete dust. Over the next three months, he endures five operations and ultimately an above-knee amputation. Every exhibit in this guide could belong to that single case.

The chapters that follow are organized by visual phase—from the first emergency photos to the final prosthetic fitting. For each phase you’ll see:

- Medical Description translates the image into plain English,

- Legal Interpretation linking that medicine to statutory proof,

- Trial Use Tip describing how to present the evidence, and

- Cross-Examination Insight showing how to confront a defense expert.

The intent is not to create new law but to equip litigators with a structure that survives cross and resonates with jurors.

Table of Contents

Medical and Anatomical Overview

A. Anatomy and Function

The right leg is a weight-bearing column that absorbs impact with every step. It contains:

- the femur, the body’s strongest bone,

- the tibia and fibula, paired bones of the lower leg, and

- connecting joints at the hip, knee, and ankle.

Muscles of the quadriceps and hamstring groups provide propulsion; the gastrocnemius and soleus power push-off. Major vessels—the femoral and popliteal arteries—supply oxygenated blood. When those vessels are torn, ischemia sets in within minutes. The nerves running alongside, particularly the tibial and peroneal, control foot motion and sensation. Damage to either changes gait permanently.

A jury need not memorize anatomy; it only needs to understand that the leg is a closed hydraulic system—break the bones and the plumbing fails.

B. Mechanisms of Injury

Right-leg trauma usually stems from high-energy forces:

- Motor-vehicle collisions: lateral impact compresses the leg between the dashboard and firewall.

- Pedestrian strikes: bumper height aligns with the tibia, creating predictable mid-shaft fractures.

- Construction falls or crushes: heavy equipment or rebar cages crush soft tissue before the patient even reaches the hospital.

- Industrial rollovers: the leg is trapped under machinery, leading to degloving and vascular injury.

Each mechanism leaves its signature pattern. Photographs showing road rash, steel imprints, or gravel contamination help medical witnesses describe the energy involved—proof that this was no “minor” impact.

C. Initial Management

At the trauma-bay level, priority is bleeding control and perfusion. Tourniquets buy time but cost tissue viability. The orthopedic team irrigates and debrides, removing debris and dead muscle until healthy tissue bleeds freely—a concept jurors can grasp when explained simply: “If it doesn’t bleed, it can’t live.” External fixation follows to realign bone and allow swelling to subside. IV antibiotics start immediately.

If pulses do not return, vascular surgeons attempt repair. When repair fails, amputation becomes the only option. Each decision is documented in operative notes that later anchor causation testimony.

D. Complications and Sequelae

Even with ideal care, catastrophic leg injuries carry high complication rates:

- Infection and osteomyelitis. Once bacteria reach bone, complete eradication may take months.

- Compartment syndrome. Swelling cuts off circulation, requiring fasciotomy incisions that scar from knee to ankle.

- Non-union. Bone ends refuse to knit despite hardware; surgeons must graft or re-plate.

- Nerve damage. Leads to chronic pain and sensory loss.

- Psychological trauma. PTSD and phantom-limb pain affect more than 60 % of amputees.

Each complication extends hospitalization and multiplies damages. What matters for litigation is not only that these outcomes occur, but that they are foreseeable consequences of the original negligence.

E. Rehabilitation and Prosthetic Dependence

Physical therapy begins within days of surgery. Early motion prevents stiffness but amplifies pain. Once an amputation stabilizes, prosthetic training starts. Modern microprocessor knees restore mobility, yet they require replacement every few years and constant maintenance. The client never again experiences the natural feedback of a biological leg. Demonstrating that fact to a jury turns abstract disability into tangible loss.

Trial Hypothetical:

Imagine a 32-year-old delivery driver who returns to work using a prosthesis. Defense argues “he’s back on his feet.” Cross-examination should focus on what jurors can see: the harness marks, the socket rash, the daily battery charge, the weather limitations. Recovery is not the same as restoration.

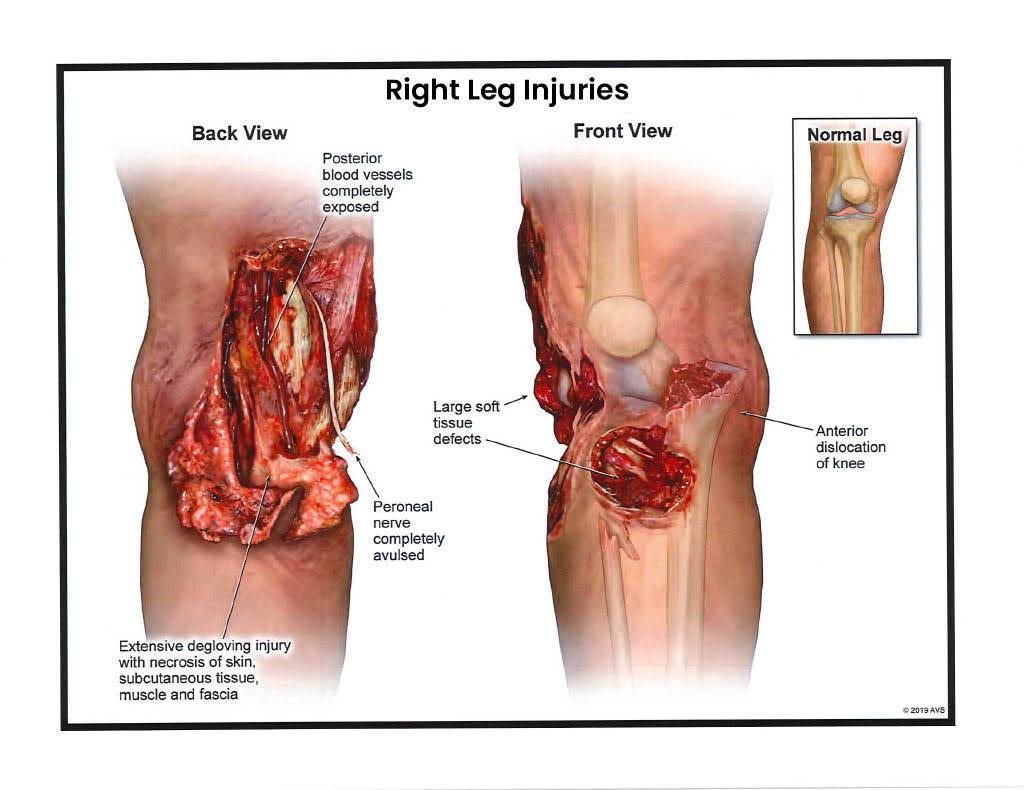

Exhibit A — Right Leg Injuries (Front and Back Views)

Medical Description

The first images show the moment of truth in catastrophic limb trauma: the right leg mangled from mid-calf to ankle, bone and tendon visible, skin sheared away. The pattern—deep anterior laceration with exposed tibia and posterior degloving—is consistent with a high-energy crush or rollover mechanism. Trauma surgeons classify this as a Gustilo Type III-C open fracture: compound fracture with vascular injury requiring repair. The popliteal artery has likely been transected; perfusion is gone. Even with aggressive debridement and re-vascularization, the odds of salvage are slim. Infection, necrosis, and amputation loom from the start.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)

For threshold analysis, this exhibit is your foundation. Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), it represents a permanent loss of use of a body member and significant disfigurement. In New Jersey, the same wound crosses at least three AICRA categories—dismemberment, displaced fracture, and permanent injury within a reasonable degree of medical probability. It visually eliminates any argument that the case involves “soft-tissue” injury. A juror looking at this photograph instantly understands: no amount of therapy restores that limb to normal function.

Trial Use Tip

Use Exhibit A to open the medical narrative, not to shock. Display it briefly, with the treating surgeon or trauma specialist explaining calmly what the image shows: the absence of viable tissue, the immediate threat to life, the surgical urgency. Project it once, then replace it with a line drawing or x-ray to keep jurors engaged without desensitizing them. Remind the court that this isn’t a photograph of gore—it’s evidence of causation. The power lies in restraint; overexposure risks numbing your audience.

Cross-Examination Insight

Defense experts often float the idea of “limb salvage.” Box them in with perfusion questions:

- “Doctor, do you see arterial pulsation here?”

- “Would you expect this muscle to survive without blood flow?”

- “Can an orthopedic surgeon heal bone that’s already necrotic?”

Their answers reduce speculation to fact—the limb was lost the moment the steel met bone.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 38-year-old cyclist struck by a delivery van arrives with a wound identical to this. The trauma team performs four hours of surgery before declaring the leg unsalvageable. At trial, counsel introduces Exhibit A with one sentence: “This is the leg they tried—and failed—to save.” The jury needs no further explanation.

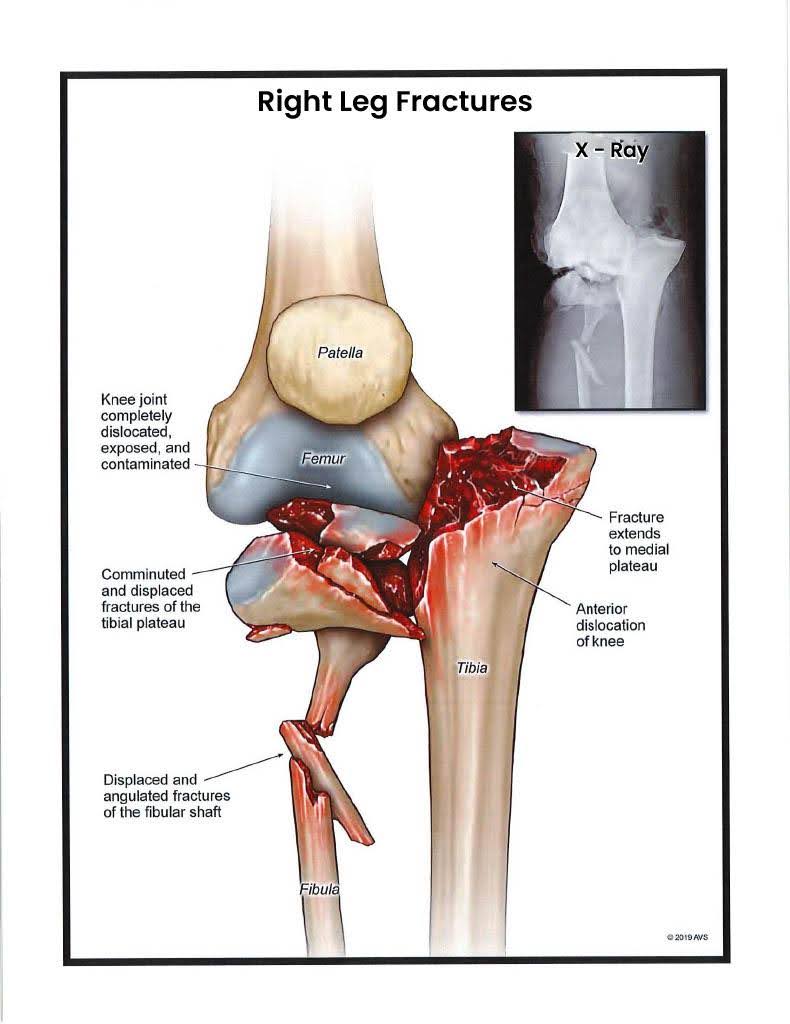

Exhibit B — Right Leg Fractures (X-ray)

Medical Description

Exhibit B presents the interior view that confirms what Exhibit A hinted at. The anterior–posterior and lateral radiographs show comminuted mid-shaft fractures of both the tibia and fibula. The tibia, normally a clean vertical column, is fragmented into multiple displaced pieces with complete cortical discontinuity. The fibula splinters in two distinct zones—a “segmental” pattern seen when rotational and compressive forces act together. The spacing between fragments indicates loss of bony length; the limb has effectively shortened. This configuration demands surgical fixation with plates, screws, or intramedullary rod, but infection risk and soft-tissue loss complicate every choice. Radiology provides the cold, objective truth of trauma: bone architecture destroyed beyond natural repair.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)\

Radiographs are your most credible proof of a displaced fracture. Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), that displacement and loss of alignment satisfy the “significant limitation of use” and “permanent consequential limitation” categories. In New Jersey, AICRA § 39:6A-8(a) lists displaced fracture as an independent gateway to non-economic recovery—no further permanency proof required. Exhibit B removes debate: this is no “sprain” or “strain.” Even after surgical stabilization, the leg’s mechanical integrity and load-bearing capacity are permanently compromised. Jurors can literally see the break; they don’t have to take anyone’s word for it.

Trial Use Tip

Show this image immediately after the initial wound photos. Tell the jury, “Now we move from what you can see to what the x-ray saw.” Use a split-screen comparison: left side a normal tibia, right side this shattered one. Ask the orthopedic expert to trace the fracture lines with a light pen. Keep it simple—“This piece belongs here, this one here.” Avoid medical jargon like comminution; translate to multiple breaks. When jurors nod, you know they understand causation.

Cross-Examination Insight

Defense IMEs often testify that post-operative films show “good alignment.” The counter is to focus on original trauma: “Doctor, alignment after surgery tells us skill, not severity—correct?” Then walk them back to Exhibit B. “Before the surgery, where was the bone?” Their concession—“in multiple pieces”—restores the narrative of catastrophic force.

Trial Hypothetical:

In a delivery-truck impact, the plaintiff’s tibia looked identical. Defense called it a clean break. Counsel displayed an x-ray enlargement, pointed to the half-inch gap, and asked, “Does ‘clean’ mean missing?” The jurors laughed softly—not at humor, but at clarity. The fracture spoke for itself.

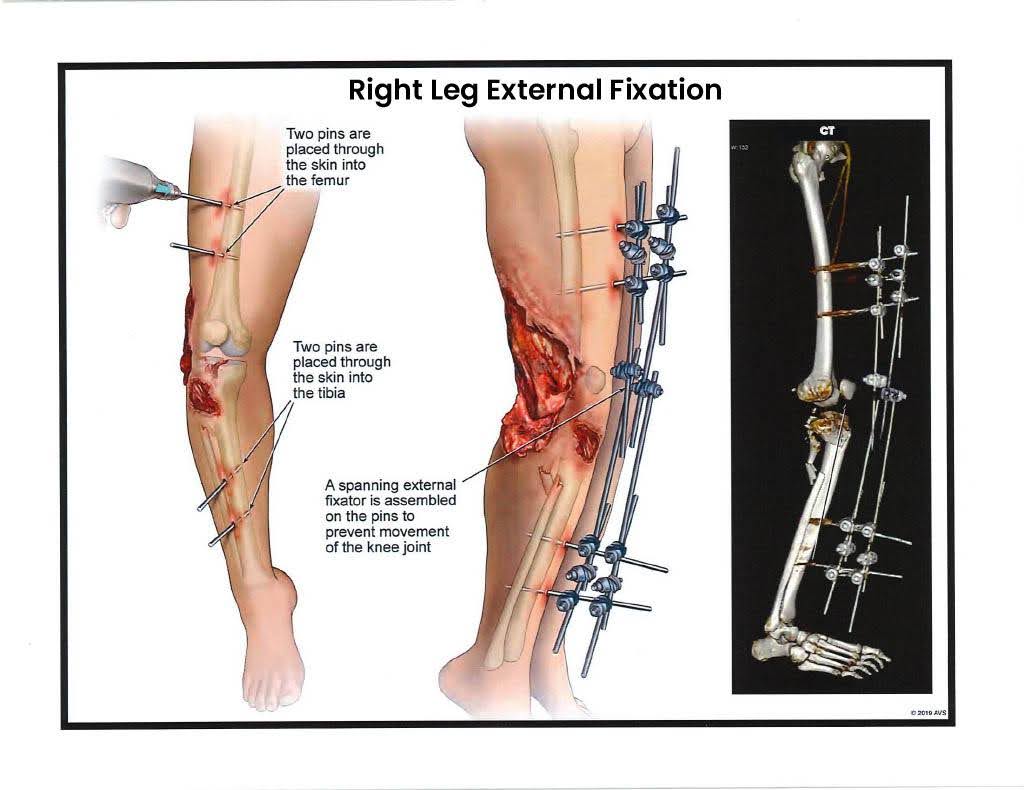

Exhibit C — Right Leg External Fixation (CT View)

Medical Description

Exhibit C captures the immediate post-operative reality of a limb held together by hardware rather than bone. Long, stainless-steel pins pierce the skin at right angles, anchoring into the tibia and fibula and connecting to an external frame. The rods form a rigid cage, keeping bone fragments aligned while the soft tissue heals. Every pinhole is a wound that can harbor bacteria; each turn of an adjustment wrench creates pain. Patients live with this scaffolding for weeks or months—sleeping, showering, and even commuting with metal bars protruding from the flesh. A computed-tomography slice shows the rods traversing cortical bone, confirming the precision of placement but also the invasiveness of the procedure. This is orthopedic carpentry at its rawest: the body stabilized by steel.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)

External fixation is the physical embodiment of “serious injury.” Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), the necessity of surgically inserted hardware proves both significant limitation of use and permanent consequential limitation. In New Jersey, it demonstrates medical treatment “consistent with displaced fracture” and a permanent injury within a reasonable degree of medical probability under AICRA § 39:6A-8(a). The photograph alone communicates duration of suffering: the patient cannot walk, bathe normally, or sleep without risk of infection. The frame becomes a visual yardstick for pain and recovery time—jurors instinctively know that bones requiring a cage are not minor injuries.

Trial Use Tip

Introduce Exhibit C through the treating orthopedic surgeon. Start with calm explanation—how alignment is maintained, how often adjustments occur. Then segue to the human element: “Each of these bolts crosses healthy tissue before reaching bone.” Use a simple model or even a spare pin to demonstrate length; tangible objects deepen understanding. Keep the image on screen only as long as it takes for jurors to absorb the engineering. Replace it with the next step—post-fixation therapy—to maintain forward momentum.

Cross-Examination Insight

Defense experts often call the fixator “temporary stabilization.” Agree—then redefine “temporary.” “Doctor, in your practice, does temporary mean six weeks of hardware through skin and bone?” Pause. “During those six weeks, could the patient bear weight?” Their “no” concedes the functional loss. If they claim minimal pain, refer to hospital records listing daily narcotics. Objective data trumps speculation.

Trial Hypothetical:

A warehouse worker crushed between pallets spent eight weeks with an external frame. At trial, counsel held up a replica pin, explaining, “He had six of these driven through his leg.” A juror later said that single demonstration made the injury real. Exhibit C delivers that same authenticity—the steel that kept a leg in one piece.

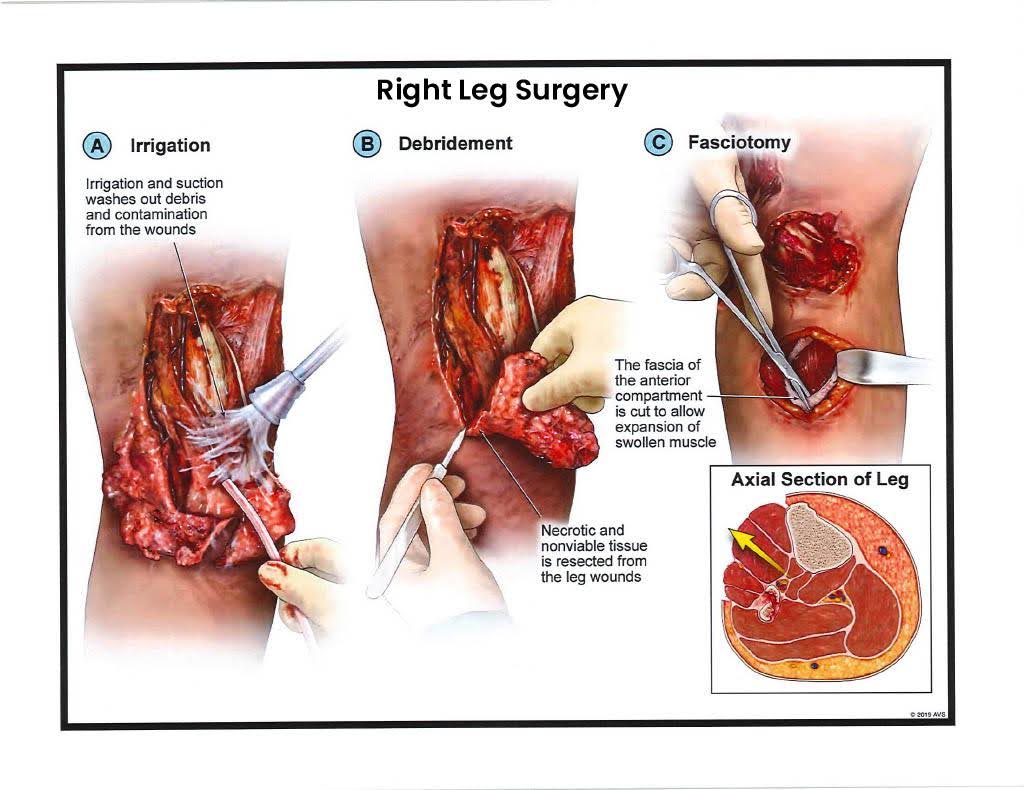

Exhibit D — Right Leg Surgery – Debridement and Fasciotomy

Medical Description

Exhibit D shows the next phase of surgical battle—the effort to save living tissue from the crush of swelling and infection. Two long, vertical incisions extend from knee to ankle, running parallel along the calf. These cuts are called fasciotomies: they release the internal pressure that builds within muscle compartments after trauma. Without this release, circulation stops and the tissue suffocates from the inside out. The photo also reveals excised, necrotic skin around the tibia, with visible sutures holding drains in place to evacuate fluid. The patient’s leg appears swollen, shiny, and segmented by dressing strips. Each centimeter of those openings represents an hour of emergency surgery. What the jurors see is not gore but anatomy fighting physics—the attempt to keep muscle alive long enough to heal.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)

In legal terms, this stage of care transforms the injury from severe to catastrophic. Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), the necessity of surgical fasciotomy establishes a significant limitation of use and permanent consequential limitation; under New Jersey’s AICRA § 39:6A-8(a), the same procedure supports significant disfigurement and permanent injury. Every incision marks permanent alteration. The scars alone qualify as visible disfigurement, while the underlying muscle loss proves permanent impairment. Moreover, repeated debridements show that the plaintiff remained compliant, following every medical order to avoid amputation—facts that strengthen causation and rebut comparative fault arguments.

Trial Use Tip

This exhibit works best mid-testimony, once the jury understands initial stabilization. Introduce it with the treating surgeon’s matter-of-fact explanation: “We had to open the leg to relieve pressure—without this, he’d lose it entirely.” Use a medical illustration to trace the compartments being released so jurors can follow visually without shock. Keep the camera zoomed out; distance preserves professionalism. When closing, reference this photo as “the surgery that gave him a chance,” emphasizing necessity, not spectacle.

Cross-Examination Insight

Defense experts sometimes minimize fasciotomy as “precautionary.” Undermine that phrasing gently:

- “Doctor, precautionary means optional, correct?”

- “Would you call a life-saving incision optional?”

If they concede necessity, the point is won; if they resist, the record of rising compartment pressures speaks louder. When asked calmly, those two questions turn semantics into credibility.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 29-year-old ironworker crushed by falling scaffolding undergoes identical fasciotomy incisions. At trial, counsel described them as “the surgeries that bought him time.” The jury understood: these wounds were not cosmetic—they were proof of life. Exhibit D tells the same truth in every case.

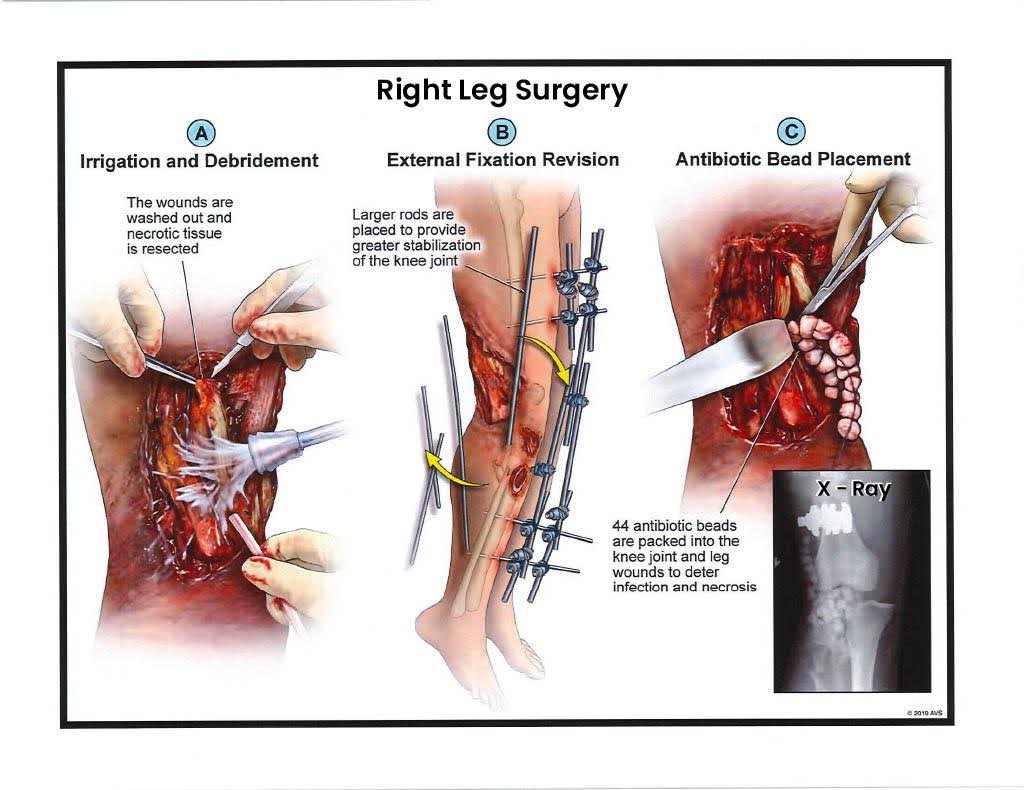

Exhibit E — Right Leg Surgery – External Fixation Revision

Medical Description

Exhibit E shows the midway point of a long fight against infection. After weeks of wearing an external frame, the patient develops drainage around several pin sites. Bacterial cultures identify Staphylococcus aureus—a hospital-acquired infection common in open fractures. To control it, surgeons remove the contaminated hardware and re-insert new fixation pins through different tracts. They then pack the voids with small white spheres—antibiotic beads made of calcium sulfate or polymethyl-methacrylate mixed with vancomycin or gentamicin. Each bead slowly releases medication, bathing the wound from within. The photo displays a patchwork of old scars, new incisions, and clear tubing for irrigation. To the untrained eye, it looks chaotic; to the surgeon, it is controlled desperation—one last effort to sterilize the bone before it dies.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)

This stage provides powerful proof of complication, compliance, and causation. Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), repeated revision surgeries and hardware removal constitute a permanent consequential limitation of use; in New Jersey, the same sequence demonstrates permanent injury and significant disfigurement under AICRA § 39:6A-8(a). The plaintiff followed every medical directive—multiple hospitalizations, IV antibiotics, and invasive procedures—yet infection persisted. That chronology defeats any defense suggestion of “failure to mitigate.” It also builds damages: each operation adds bills, pain, and recovery time. The law rewards diligence, and Exhibit E shows diligence made visible.

Trial Use Tip

Place this exhibit in the middle of your medical timeline, roughly two-thirds of the way through direct examination. By now jurors grasp the seriousness; what they need is endurance. Have the orthopedic surgeon explain the purpose of the beads in plain language—“They act like tiny medicine pumps inside the bone.” If possible, display an actual sterile bead during testimony. Tangible props make the abstract concrete. Keep tone clinical, not dramatic: jurors respect precision over pathos.

Cross-Examination Insight

Defense witnesses often label the infection “minor” or “superficial.” Ask factual, binary questions:

- “Was the patient admitted to the hospital for this infection?”

- “Did treatment require anesthesia?”

- “Were antibiotic beads inserted into the bone?”

Each “yes” contradicts “minor.” Close with, “So this was a surgical infection, correct?” The witness’s concession reframes the defense narrative into your own.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 45-year-old delivery driver develops identical pin-tract infection after external fixation. He spends three additional weeks hospitalized for IV antibiotics. At mediation, opposing counsel calls it “a short delay.” Plaintiff’s counsel lays out the operative photos and says, “That’s three weeks of living with open holes in his leg.” The case settles within hours. Exhibit E delivers the same reality check in any courtroom.

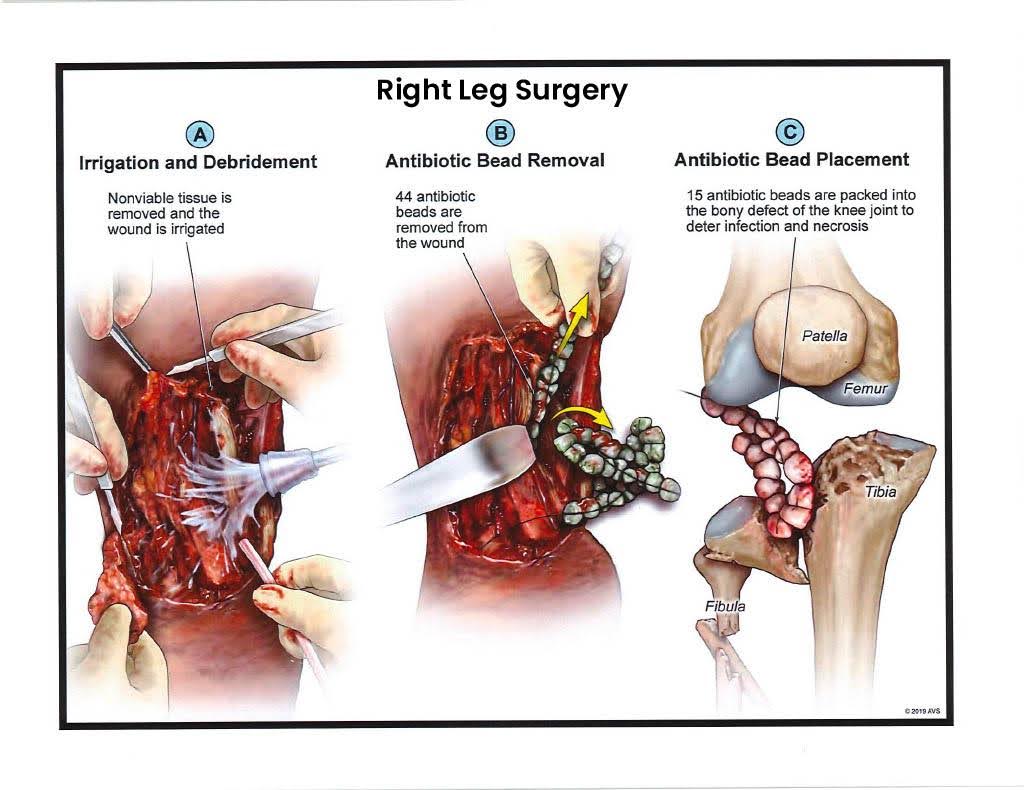

Exhibit F — Right Leg Surgery – Bead Removal

Medical Description

Exhibit F marks the final surgical crossroad. The patient has endured months of fixation, debridement, and antibiotic therapy, yet the infection persists. The photograph shows the leg after removal of antibiotic beads—an operation meant to determine if any viable tissue remains. The skin edges appear pale; the muscle underneath is dull gray instead of healthy red, a sure sign of necrosis. The vascular graft attempted earlier has failed, leaving the distal limb without perfusion. Drains exit from multiple points, and surgical markers indicate planned incision lines for amputation. The attending note for this stage typically reads, “Persistent infection and loss of soft-tissue coverage—amputation recommended for definitive management.” At this moment, medicine gives way to inevitability: the goal is no longer saving the leg but saving the life.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)

Legally, this exhibit closes the loop between negligence and permanency. Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), it confirms a permanent loss of use of a body member. In New Jersey, it satisfies at least three AICRA § 39:6A-8(a) categories—dismemberment, displaced fracture, and permanent injury. What matters is not simply that amputation occurred, but that it followed exhaustive medical effort. This photograph is visual proof of compliance: multiple surgeries, full cooperation, and no alternative left. It rebuts any argument that the plaintiff “gave up” or “chose amputation.” It also strengthens the damages case by showing the human cost of prolonged suffering—weeks of wound care, IV antibiotics, and pain—all leading to the same unavoidable result.

Trial Use Tip

Exhibit F should bridge the jury from the salvage attempt to the amputation itself. Show it after establishing the infection timeline but before unveiling the amputation image. Have the treating surgeon explain that this was the last chance. Use neutral phrasing: “At this point, circulation was gone.” Avoid adjectives like “horrific”; professionalism carries more weight. When the jury sees this image, they should feel inevitability, not theatrics. A simple caption on a poster board—“Day 92: Still No Blood Flow”—can summarize volumes.

Cross-Examination Insight

Defense experts may suggest patient non-compliance. Counter with specifics:

- “Doctor, did infection persist despite hospitalization?”

- “Were IV antibiotics administered daily?”

- “Would better effort restore circulation without arteries?”

Each question narrows the path until their only answer is no. Let the record, not emotion, show cooperation.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 42-year-old construction laborer faces this same juncture after four months of treatment. He asks his surgeon, “If we keep trying, what are my chances?” The reply: “Less than ten percent—and you could die of sepsis.” That exchange becomes the heart of the trial narrative. Exhibit F conveys that moment of forced surrender with unmistakable clarity.

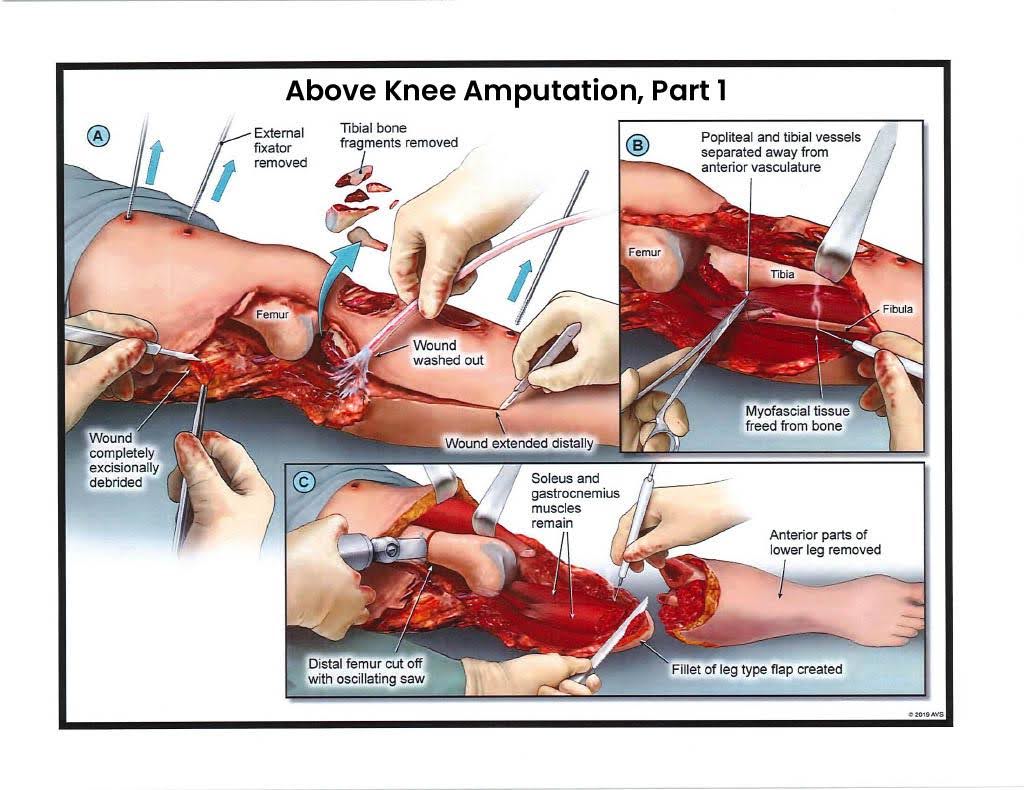

Exhibit G — Above Knee Amputation – Part 1

Medical Description

Exhibit G documents the moment medicine and reality meet. The image shows the limb removed several centimeters above the patella. The femur lies exposed, freshly transected, surrounded by retracted quadriceps and hamstring tissue. Surgeons have begun a myodesis, suturing muscle to bone so the stump can later tolerate a prosthetic socket. The operative field is stark—clean, deliberate, and decisive. Drains prevent fluid accumulation; cauterized vessels reveal the final control of bleeding. For jurors, this photo ends the question of “How bad was it?” There is no more leg. Every surgery, every infection, every sleepless night led here.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)

This exhibit visually satisfies every statutory definition of “serious injury.” Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), an above-knee amputation is the textbook example of permanent loss of use and significant disfigurement. Under New Jersey’s AICRA § 39:6A-8(a), it falls squarely within dismemberment and permanent injury within a reasonable degree of medical probability. The causal chain is clear and unbroken: negligence → crush injury → infection → vascular failure → surgical removal. Nothing about this photo is speculative or subjective. It is the physical definition of permanency.

Trial Use Tip

Use Exhibit G sparingly and with purpose. Introduce it through the treating surgeon, not the client. The tone should be factual, not dramatic: “This is the operative photo confirming amputation.” Allow jurors a few seconds of silence; it lets the reality sink in without commentary. Then immediately shift to the next exhibit showing closure and recovery, so the focus moves from loss to survival. If presented properly, the image earns empathy, not pity. Always pre-clear the photo with the judge during motion in limine to prevent claims of prejudice—its probative value far outweighs any emotional risk.

Cross-Examination Insight

Defense witnesses sometimes imply that amputation was “elective” or “patient-driven.” Reduce that claim to absurdity.

- “Doctor, when a limb has no blood flow, is amputation optional?”

- “Can necrotic bone regenerate?”

- “Would any reasonable surgeon decline to operate in this situation?”

Once answered, those questions lock the jury’s understanding: this surgery was not a choice; it was the only option.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 36-year-old truck mechanic arrives at trial in dress slacks concealing his prosthesis. Counsel introduces Exhibit G, stating simply, “This is how he got here.” No adjectives, no dramatics—just fact. The jurors stare, nod once, and the silence that follows is worth more than a thousand words.

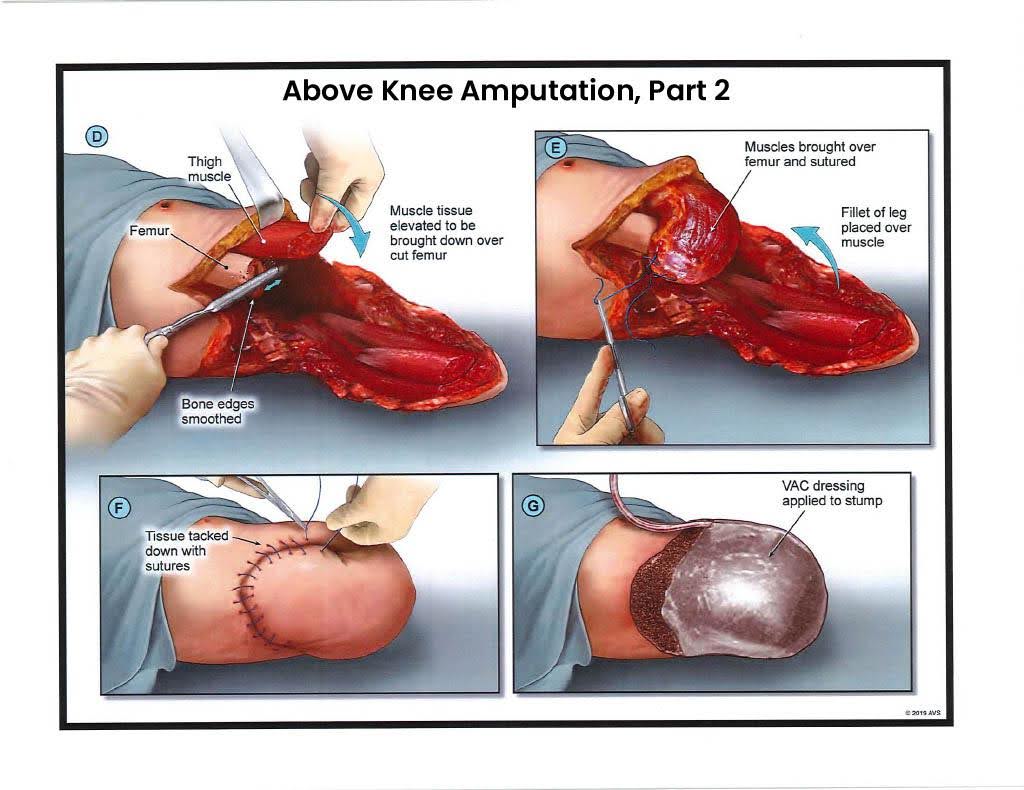

Exhibit H — Above Knee Amputation – Part 2

Medical Description

Exhibit H shows the surgical closure following the above-knee amputation. The operative field now appears orderly—flaps of anterior and posterior thigh skin have been rotated and sutured together to cover the bone end. The stump, or residual limb, is conical and carefully contoured to accept a future prosthetic socket. A drain exits laterally to prevent fluid accumulation beneath the incision, and the dressing is secured with compression wraps to shape the limb as it heals. Despite the apparent calm of this image compared to Exhibit G, the trauma remains absolute. Beneath the staples, nerves have been shortened and buried within muscle, yet they continue to fire errant pain signals—a phenomenon called phantom limb pain. The patient awakens feeling as though the missing leg still burns. This is the paradox of success in trauma surgery: the procedure saves life at the cost of identity.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)

Legally, this exhibit cements permanency, disfigurement, and functional loss. Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), there is no question of threshold; this is permanent loss of use of a body member and significant disfigurement visible to the average observer. In New Jersey, the amputation squarely meets the dismemberment and permanent injury categories under AICRA § 39:6A-8(a). Moreover, Exhibit H illustrates continuing medical consequences—stump care, skin breakdown, revision surgeries, prosthetic dependence. It provides the jury with tangible proof that even after the surgical “success,” disability persists.

Trial Use Tip

Exhibit H should transition the jurors from the shock of loss to the reality of adaptation. Present it during expert testimony on recovery or rehabilitation. Keep the tone clinical: “This is the closure. The wound must now heal for prosthetic fitting.” Avoid emotional descriptors; let the image speak through professionalism. If you have the earlier photograph (Exhibit G) in their minds, this one shows progress and resilience. For CLE presentations or peer education, it’s an effective visual to discuss wound-healing timelines and prosthetic readiness.

Cross-Examination Insight

Defense witnesses sometimes claim “excellent recovery.” Acknowledge it—then frame it.

- “Doctor, an excellent recovery from amputation still means no natural leg, correct?”

- “Would you agree that skin closure does not restore joint movement or sensation?”

These questions transform optimism into realism. The leg is gone; no amount of good healing changes that fact.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 40-year-old electrician returns to the courtroom six months post-op, walking with a prosthetic. Defense calls this “full recovery.” Counsel shows Exhibit H and says, “Recovery means this healed. It doesn’t mean he got his leg back.” The jury nods. The distinction—simple but powerful—anchors the value of the case.

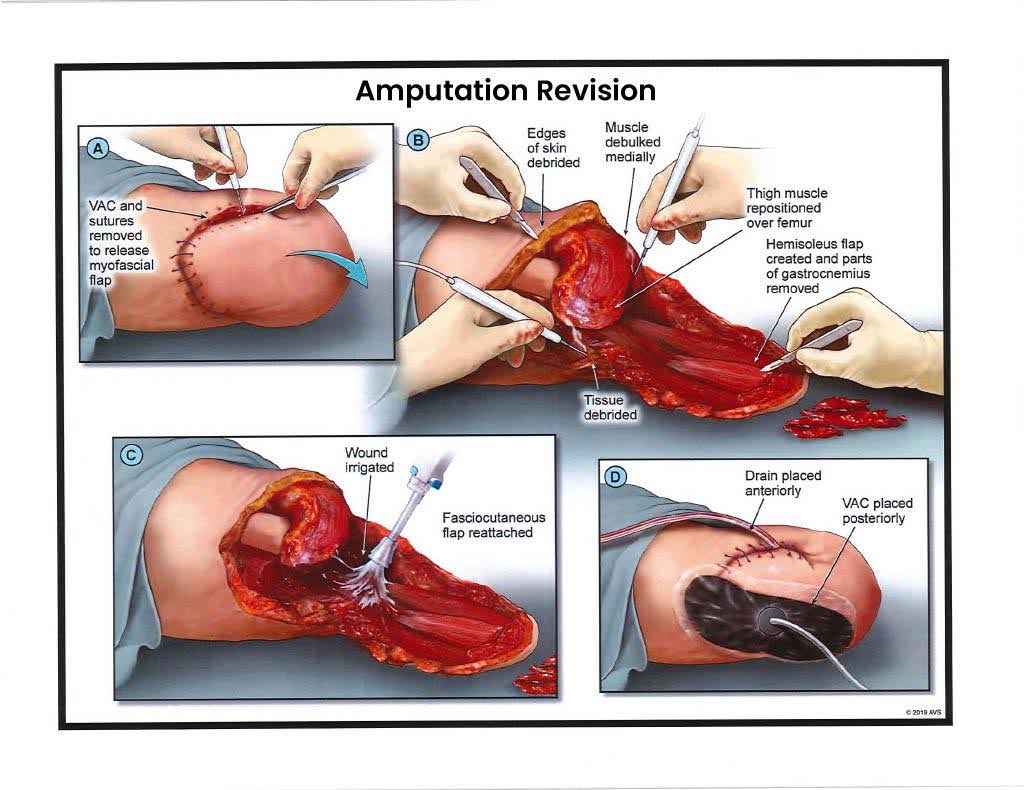

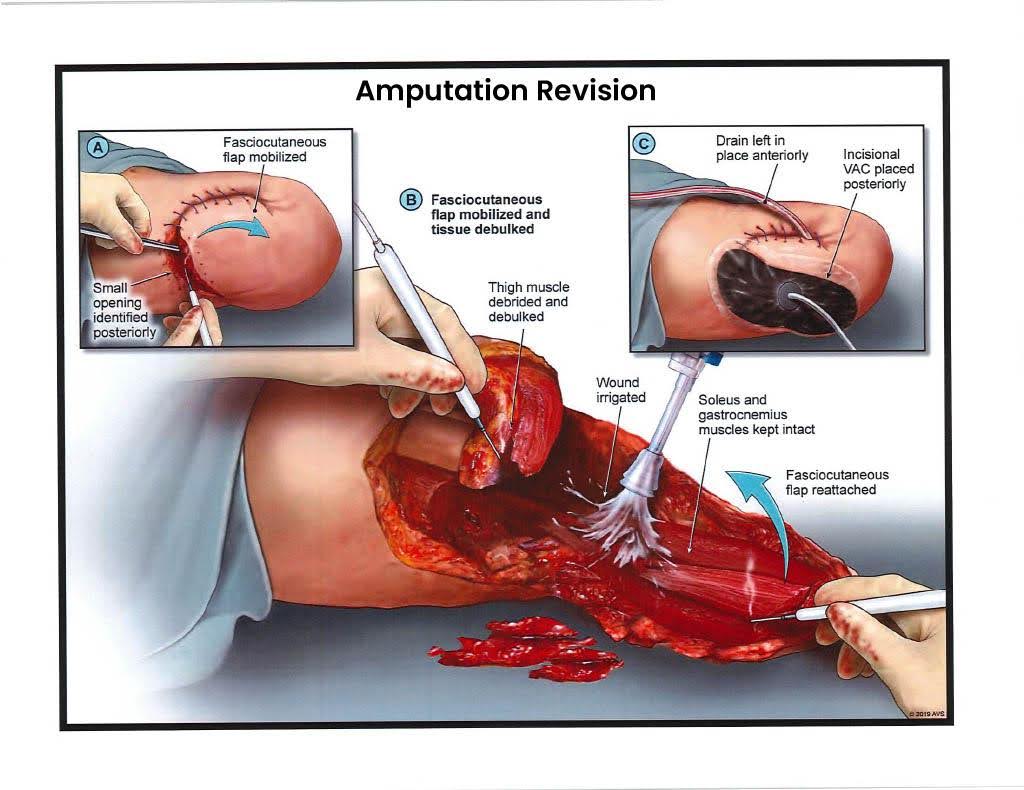

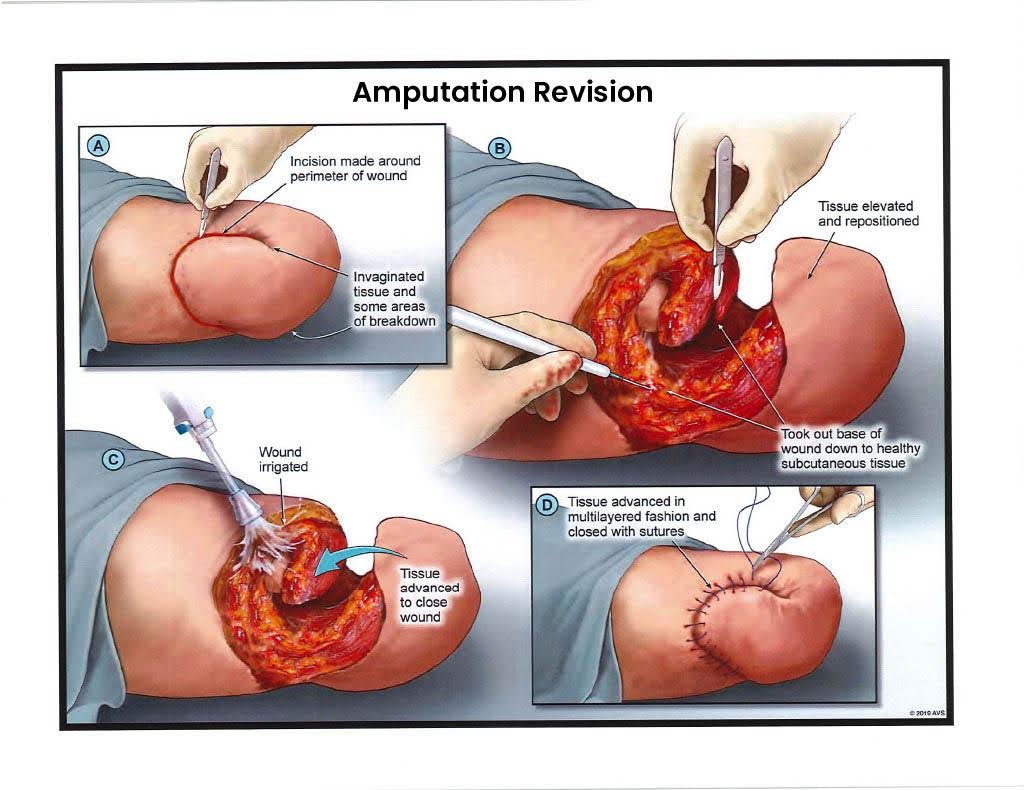

Exhibit I — Amputation Revision – Stage 1

Medical Description

Exhibit I depicts the first revision surgery following the initial amputation. Revision procedures are not uncommon in traumatic amputations; they are necessary when infection, poor healing, or tissue necrosis prevents full closure. In this photograph, the surgical team has reopened the wound along the prior incision line. The edges appear inflamed and irregular, a sign of tissue breakdown and bacterial colonization. The surgeon has excised a ring of nonviable skin and muscle to reach healthy, bleeding tissue. The femoral stump has been slightly shortened to allow better flap coverage. A negative-pressure dressing—often called a wound VAC—is in place to draw out fluid and promote healing by suction. What looks, at first glance, like a setback is actually an essential part of the recovery sequence. Each revision carries risk: anesthesia, further blood loss, and prolonged immobility. For the patient, it’s another hospitalization and another reminder that the trauma isn’t over.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)

From a legal standpoint, revision surgery strengthens the proof of permanency and continuing disability. Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), additional operations following amputation show that the limitation of use is not temporary but enduring. Under New Jersey’s AICRA § 39:6A-8(a), the need for further surgery confirms a permanent injury within a reasonable degree of medical probability. Exhibit I also defeats any suggestion that the plaintiff’s condition stabilized quickly or that recovery was complete. Each revision adds medical bills, pain, and lost time from rehabilitation—elements directly relevant to economic and non-economic damages.

Trial Use Tip

Use Exhibit I to show the jury that healing is not linear. Introduce it through the treating surgeon or wound-care specialist. Let them explain that this kind of setback is common in high-energy trauma, not the result of negligence by the patient. On a timeline poster, mark this event clearly—it helps jurors see the months of endurance between the amputation and final closure. Keep tone factual, not dramatic. Jurors respect persistence more than pity.

Cross-Examination Insight

If defense counsel suggests the revision was “elective,” counter with narrow, surgical questions:

- “Doctor, was this surgery scheduled for convenience or medical necessity?”

- “What happens if necrotic tissue is left unremoved?”

Once the expert admits that infection can become systemic, the jury understands: this was life-saving, not cosmetic.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 52-year-old factory worker undergoes a revision after stump infection. Defense calls it “routine.” On redirect, plaintiff’s counsel asks, “How many routine procedures require general anesthesia and two days in the ICU?” The answer—“none”—reframes the event immediately. Exhibit I makes that reality visible.

Exhibit J — Amputation Revision – Stage 2

Medical Description

Exhibit J shows the second major revision of the residual limb, performed after the first revision failed to achieve durable closure. The photograph reveals a clean but freshly reopened field: healthy muscle exposed, edges re-trimmed, bone shortened another centimeter to remove residual osteomyelitis—an infection of the marrow that no antibiotic alone can cure. The surgeon re-balances the soft-tissue envelope, rotating a muscle flap from the posterior thigh to cover the bone. This “myoplasty” adds padding for future prosthetic use but sacrifices strength. The drain and wound-VAC tubing visible in the photo underscore that healing remains fragile. Revision after revision taxes both body and spirit: each operation restarts the clock on rehabilitation. Patients describe the experience as “one step forward, two steps back.” Clinically, that is accurate.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)

Every additional revision deepens the evidentiary record of permanent injury and ongoing medical impairment. Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), multiple revision surgeries constitute clear proof of permanent consequential limitation—the leg cannot sustain weight or motion in its natural form. Under New Jersey’s AICRA § 39:6A-8(a), repeated operations satisfy the permanent-injury threshold and strengthen claims for both economic and non-economic damages. The plaintiff’s compliance—returning for each surgery, following wound-care protocols—negates any inference of contributory fault. Exhibit J also bolsters credibility; jurors see tangible persistence, not exaggeration. This is medical perseverance documented in surgical photographs.

Trial Use Tip

Place Exhibit J late in your medical chronology, before transitioning to the final revision or prosthetic-fitting exhibits. Use it to emphasize the duration and relentlessness of treatment. Have the surgeon testify: “We removed infected bone; it was the only way to make the stump safe for a prosthesis.” Keep a running total of hospital days on a visual timeline—by now, jurors grasp the cumulative toll. For CLE audiences, this image demonstrates the concept of delayed closure and why “amputation cases” don’t end with amputation.

Cross-Examination Insight

Defense experts sometimes label repeated revisions “typical.” Accept the term, then expose its meaning.

- “Doctor, typical for whom—the average sprained ankle or the catastrophic trauma patient?”

- “Would you agree that each revision adds cost and pain?”

Those two answers are enough: jurors understand “typical” still means terrible. Follow with medical-record references to confirm infection cultures or bone shortening, anchoring opinion in fact.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 47-year-old carpenter undergoes this same second revision. Defense contends it was “over-treatment.” On cross, counsel asks, “If your patient’s bone were infected, would you leave it inside?” The orthopedic expert pauses, then answers, “No.” That pause is worth thousands. Exhibit J captures exactly why revision isn’t optional—it’s survival, one surgery at a time.

Exhibit K — Amputation Revision – Stage 3

Medical Description

Exhibit K captures the final revision surgery—an operation that represents both closure and exhaustion. After months of repeated infections and tissue failures, the surgical team performs a definitive revision. The femur has been shortened to a stable, healthy segment. The image shows new muscle flaps from the posterior and lateral thigh drawn forward to cushion the bone. The tissue is fresh and well perfused, the color deep red instead of pale gray—an encouraging sign. Multiple sutures secure the new closure, and a compressive dressing controls swelling. At the base of the stump, a small tube indicates continued use of negative-pressure wound therapy to ensure fluid evacuation. Although this procedure looks calm and controlled, the toll on the patient is enormous: multiple anesthesias, blood transfusions, and months of immobility. Even when this final closure succeeds, residual limb pain and phantom sensations persist indefinitely. Rehabilitation can finally begin, but the road ahead is lifelong.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)

In legal analysis, Exhibit K completes the narrative of permanency and causation. Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), the final revision proves the plaintiff’s impairment is not transient—it is a permanent, consequential limitation requiring ongoing care. Under New Jersey’s AICRA § 39:6A-8(a), the repeated surgical sequence culminating in this final revision satisfies the permanent-injury standard beyond doubt. Each revision, and especially this one, reflects foreseeable consequences of the initial trauma. The plaintiff’s compliance and medical perseverance are now undeniable, insulating the case from claims of negligence or noncompliance. Jurors will recognize the persistence required to reach this stage. Damages—economic and human—accrue with every incision.

Trial Use Tip

Exhibit K should serve as the pivot to your prosthetic and rehabilitation exhibits. When presenting it, frame it as the final step before restoration of mobility: “This surgery finally closed the wound, allowing him to start learning to walk again.” The phrasing balances empathy with professionalism. Visual aids can include a simple timeline: date of injury to date of this closure, demonstrating the year-long battle to stabilize the stump. Use this as the moment to transition from medical intervention to life adjustment—jurors need closure just as the patient does.

Cross-Examination Insight

Defense experts occasionally argue “successful outcome,” implying resolution. Agree with the premise, redefine the success:

- “Doctor, successful in the sense that the wound closed, not that the leg returned—correct?”

- “Would you call living with a shortened femur and nerve pain a full recovery?”

Polite tone, short questions—the witness’s answers will reveal the truth.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 33-year-old delivery driver reaches this third revision after nine months of treatment. Defense argues “miraculous recovery.” Plaintiff’s counsel displays Exhibit K and responds, “Yes—miraculous that he survived all this just to learn to walk again.” The jury sees not exaggeration but endurance. Exhibit K is the visual proof of finality after chaos.

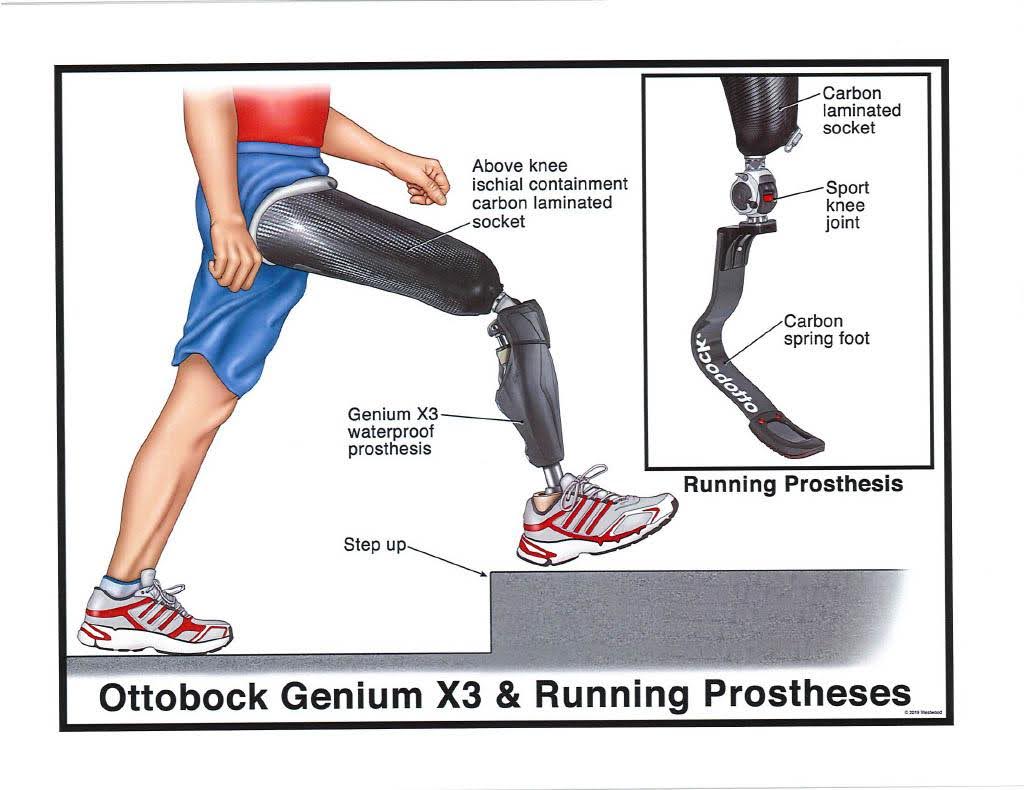

Exhibit L — C-Leg Femoral Prosthesis

Medical Description

Exhibit L depicts the transition from survival to adaptation—the patient’s first step toward restored mobility. The C-Leg, manufactured by Ottobock, is a microprocessor-controlled prosthesis that replaces the function of the knee joint. The image shows a sleek titanium frame connected to a carbon-fiber socket molded to the patient’s residual limb. Sensors within the device measure stride, acceleration, and ground contact a thousand times per second, adjusting hydraulic resistance to create a stable, natural gait. The C-Leg allows the amputee to descend stairs or navigate uneven surfaces with confidence—a feat impossible with older mechanical knees. Yet this technology is not a cure. Each socket must be custom-fitted, often requiring multiple fittings and adjustments. The limb still swells and changes shape; friction causes blistering, and skin breakdown remains a daily risk. The microprocessor knee costs between $50,000 and $70,000, with expected replacement every five to seven years. The image captures hope, but also lifelong maintenance.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)

Exhibit L provides visual evidence of permanent functional loss and future medical expense. Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), prosthetic dependency exemplifies permanent consequential limitation of use. In New Jersey, AICRA § 39:6A-8(a) recognizes the resulting disability as permanent injury within a reasonable degree of medical probability.

Economically, the cost of prosthetic devices and related care forms the backbone of the plaintiff’s life-care plan. The exhibit helps jurors connect abstract numbers to tangible equipment: this is what the medical bills purchase, and this is what will need periodic replacement forever. It also neutralizes defense arguments about “full recovery”—mobility regained is not equivalence restored.

Trial Use Tip

Use Exhibit L near the end of your medical presentation, as the pivot to damages and life impact. Have the prosthetist or rehabilitation specialist testify, demonstrating how the C-Leg functions. Short video clips or live demonstrations (if permissible) help jurors grasp the sophistication and cost. Emphasize maintenance and fragility: “If the computer fails, he can’t walk.” That single sentence encapsulates dependence. Keep the tone forward-looking but realistic—this exhibit symbolizes resilience tempered by limitation.

Cross-Examination Insight

Defense experts may argue that the prosthesis “restores normal function.” Bring them back to biology:

- “Does this device transmit sensation?”

- “Can it feel heat or pain?”

- “Does it heal when damaged?”

Each answer is “no.” Jurors learn that prosthetic legs replace motion, not humanity. Recovery is functional, never complete.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 29-year-old cyclist walks into court using a C-Leg. Defense calls it “miraculous.” Counsel replies, “It’s technology, not regeneration.” The jurors nod. Exhibit L tells that same truth—a triumph of engineering, but a permanent reminder of what was lost.

Exhibit M — Ottobock Genium X3 & Running Prosthesis

Medical Description

Exhibit M illustrates the modern frontier of prosthetic technology—the Genium X3 and specialized running prostheses. The image shows two distinct devices: on the left, the Genium X3, an advanced waterproof, sensor-driven prosthetic knee capable of dynamic terrain adaptation; on the right, a curved carbon-fiber “blade” designed for sprinting and exercise. Together they represent the dual life of an amputee: everyday mobility and active rehabilitation. The Genium’s microprocessor monitors limb position and force distribution in real time, allowing smoother gait transitions and near-natural stair climbing. However, this technology demands calibration, charging, and periodic software updates. The socket still attaches to skin and muscle through vacuum suspension—a process that leaves the user vulnerable to friction sores, sweating, and residual-limb pain. For high-activity users, running blades must be swapped manually, requiring balance and strength. These are marvels of engineering, but they are not replacements for anatomy—they are sophisticated tools that demand constant upkeep.

Legal Interpretation (NY / NJ Context)

This exhibit underscores the long-term economic and human cost of catastrophic injury. Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), lifelong prosthetic dependence constitutes permanent consequential limitation of use; under New Jersey’s AICRA § 39:6A-8(a), the ongoing need for device replacement and maintenance proves permanent injury within a reasonable degree of medical probability. The Genium X3 alone can exceed $100,000, and carbon-fiber running blades add another $20,000–$30,000, not including sockets, liners, and follow-up fittings. Exhibit M lets jurors see exactly where those figures in a life-care plan originate. It also reframes the plaintiff’s story: this is not a picture of restoration, but of adaptation at extraordinary cost. These devices allow participation in life, not a return to pre-injury normalcy.

Trial Use Tip

End your exhibit sequence with this image. It’s the natural conclusion to a journey from destruction to determination. Present it during testimony from a prosthetist or rehabilitation physician. Invite them to explain how the technology enables mobility but does not erase impairment. A brief video of the prosthesis in motion can humanize the technology. In closing, contrast this exhibit with Exhibit A—the difference between a crushed limb and a carbon-fiber replacement encapsulates the entire case narrative: from human tissue to engineered survival.

Cross-Examination Insight

Defense experts may emphasize athletic amputees as examples of “limitless recovery.” Keep the focus personal.

- “Doctor, how many of your amputee patients run marathons?”

- “Does using a $100,000 prosthesis make a patient whole again?”

The inevitable “no” grounds the discussion in reality. The devices restore motion, not sensation; independence, not identity.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 35-year-old marathoner loses his leg and trains with a Genium X3. Defense counsel projects footage of Paralympic athletes to imply parity. On redirect, plaintiff’s counsel plays the sound of the prosthesis clicking as the runner stops. “That’s not applause,” he says. “That’s the sound of maintenance.” Exhibit M symbolizes both triumph and limitation—the enduring duality of recovery after catastrophic injury.

II. Legal and Forensic Implications

The medical story of a catastrophic right-leg injury is compelling on its own, but litigation success depends on translating that medical reality into statutory satisfaction and evidentiary admissibility. This section bridges those two worlds—showing how to use the medicine to meet the law and how to avoid the pitfalls that can derail even the most sympathetic case.

A. Thresholds and Statutory Framework

New York and New Jersey share a fundamental policy goal: limiting tort recovery to genuinely serious injuries. In practice, those thresholds often decide the case before a jury ever hears it.

Under New York Insurance Law § 5102(d), a plaintiff must establish a “serious injury” to recover non-economic damages. For lower-extremity trauma, three categories dominate:

- Permanent loss of use of a body organ, member, function, or system;

- Permanent consequential limitation of a body organ or member; and

- Significant disfigurement.

An above-knee amputation or even a severely compromised limb qualifies in all three. X-rays, operative reports, and photographic exhibits convert those words from abstract criteria into tangible proof.

In New Jersey, the Automobile Insurance Cost Reduction Act (AICRA), N.J.S.A. 39:6A-8(a) restricts recovery unless one of six defined categories applies. For catastrophic leg injuries, at least four usually do: dismemberment, significant disfigurement or scarring, displaced fracture, and permanent injury within a reasonable degree of medical probability. The law requires objective medical evidence—not subjective complaints—and every exhibit from A through M provides precisely that.

The practical rule is simple: if jurors can see the injury, the threshold is met. Photographs and x-rays are inherently objective. They require no translation beyond a physician’s authentication, and they neutralize the defense refrain of “soft-tissue case.”

B. Causation and Foreseeability

For both jurisdictions, causation must be shown within a reasonable degree of medical certainty. The challenge is connecting a single moment of negligence to months of surgical sequelae. Each exhibit functions as a visual link in that chain. Exhibit A proves mechanism; Exhibits B–F demonstrate progression of infection; Exhibits G–K show medical necessity leading to amputation; Exhibits L–M establish permanency and future cost.

Defense counsel often argue “intervening causes”—infection, patient non-compliance, or surgical error. The best counter is chronology. Build a visual timeline correlating hospital records, operative reports, and photographs. Each event should flow naturally from the last, eliminating ambiguity. By trial, the jury should be able to narrate the sequence themselves. When causation feels inevitable, liability feels fair.

C. Admissibility of Photographic Evidence

The evidentiary hurdle for medical photographs is foundation, not substance. Both New York and New Jersey courts generally admit such images if they are relevant and their probative value outweighs potential prejudice. The key is authentication. The treating surgeon or record custodian should testify that the photograph fairly and accurately depicts the condition at the time of treatment. Avoid cumulative images—one strong exhibit carries more weight than ten repetitive ones. Before trial, move for an order permitting display of limited photographs as demonstrative evidence. Judges appreciate professionalism; pre-clearance signals responsibility, not manipulation. For particularly graphic images, consider grayscale or partial cropping. Jurors are less distracted by color than by context. You want comprehension, not revulsion.

D. Using Demonstratives and Timelines

Visual coherence wins complex cases. Use a medical timeline that pairs dates with corresponding exhibits. Add short, neutral captions—“Day 1: Emergency Presentation,” “Day 92: Final Debridement,” “Day 200: Amputation.” Timelines help jurors process months of hospitalization in seconds. They also reinforce causation, showing continuity between trauma and consequence. In both states, demonstrative exhibits are admissible at the judge’s discretion when they assist the trier of fact. The rule of thumb: demonstratives illustrate testimony; they don’t substitute for it. Ensure every exhibit is sponsored by a qualified witness. A clean foundation prevents later objections that can fracture your momentum mid-trial.

E. The Human Factor

Even with perfect legal foundation, juries decide cases based on credibility and humanity. The plaintiff’s perseverance—the repeated surgeries, the effort to learn prosthetic mobility—becomes the moral center of the case. Every procedural detail in Exhibits A–M reinforces that perseverance. The defense may try to minimize it; your role is to contextualize it. “This isn’t just a leg case,” you tell them. “It’s a story of every morning that starts with a socket, a battery, and a reminder.” In both New York and New Jersey, jurors respond to fairness. When they see diligence matched by suffering, they reward honesty. Law and empathy converge. The forensic exhibits prove injury; the lawyer’s restraint proves integrity.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 41-year-old construction foreman endures eleven surgeries after a scaffold collapse. Defense argues superinfection broke the chain of causation. Plaintiff’s counsel walks the jury through each exhibit chronologically. By the time Exhibit M appears, no one doubts the connection. The verdict form reads: serious injury sustained; proximate cause established.

III. Expert Witness Framework

The credibility of a catastrophic leg injury case rises and falls with the expert witness team. Jurors depend on experts not only to interpret complex medicine but also to give them permission to care—to believe that what they’re seeing is as serious as it looks. The goal is balance: technical mastery delivered with restraint. This section outlines how to select, prepare, and deploy experts effectively in New York and New Jersey leg injury litigation.

A. Core Expert Categories

- Orthopedic Trauma Surgeon:

The orthopedic surgeon is the cornerstone witness. They authenticate imaging, describe the mechanisms of injury, and explain every surgical step from fixation through amputation. Ideally, use the treating surgeon rather than a retained IME whenever possible. Treaters carry inherent credibility; they were there. In cross, defense cannot easily accuse bias because the doctor’s duty was to heal, not to persuade. If multiple surgeons were involved, designate one as the primary narrator and the others as corroborative witnesses. - Vascular or Plastic Surgeon:

These specialists explain tissue viability and the medical necessity of amputation. Their testimony establishes that the limb could not be saved without risking sepsis or death. They also rebut defense claims of “elective amputation.” A vascular expert can translate perfusion studies and operative notes into plain language for jurors, showing that once circulation was lost, the outcome was inevitable. - Prosthetist / Rehabilitation Specialist:

The prosthetist bridges medicine and daily life. They explain socket fitting, device cost, maintenance, and replacement frequency. Their testimony quantifies future damages and adds credibility to life-care plans. Forensicly, they provide the tangible context—why the $70,000 prosthesis in Exhibit L or the $100,000 Genium X3 in Exhibit M isn’t a luxury but a necessity for mobility. Jurors understand cost best when they see the equipment in motion. - Life-Care Planner and Economist: These experts complete the financial picture. The life-care planner estimates lifetime medical and prosthetic costs, while the economist reduces those costs to present value. In catastrophic leg cases, prosthetic replacement cycles, therapy, and revisions easily surpass seven figures over a lifetime. These witnesses connect medical reality to monetary accountability.

B. Sequencing and Presentation

Order of testimony matters as much as content. Open with treating physicians—they create emotional legitimacy. Follow with independent specialists who expand on prognosis and permanency. Reserve economists for last, grounding numbers in the credibility of the preceding doctors. Jurors absorb the narrative in stages: injury → treatment → adaptation → cost. That order mirrors recovery and feels intuitive.

Keep expert testimony visually reinforced. Each physician should sponsor exhibits relevant to their field:

- Orthopedist: x-rays and fixation photos (Exhibits A–F)

- Vascular/Plastic Surgeon: debridement and amputation images (Exhibits D–H)

- Prosthetist: C-Leg and Genium (Exhibits L–M)

This pairing prevents fatigue and strengthens retention. A juror who can visualize the testimony will remember it.

C. Preparation and Cross-Readiness

Before deposition or trial, invest time aligning terminology. Experts must speak like human beings, not journal authors. Replace “osteomyelitis” with “bone infection,” “fasciotomy” with “pressure release,” and “debridement” with “tissue cleaning.” Plain English disarms cross-examination and builds trust. Conduct a mock cross on every expert. Teach them to concede the obvious without resistance—“Yes, he has made progress, but progress doesn’t mean restoration.” Jurors respect humility; they distrust defensiveness.

Always script key “anchor” lines—short phrases that jurors can recall during deliberations. Examples:

- “If it doesn’t bleed, it can’t live.”

- “This prosthesis lets him move, not feel.”

- “Healing isn’t the same as being whole.”

Those lines frame the story long after testimony ends.

D. Daubert / Frye and Evidentiary Concerns

Both New York and New Jersey apply standards to ensure expert reliability, though their tests differ slightly.

- New York (Frye standard): admissibility turns on whether the expert’s methods are “generally accepted” in the scientific community. Orthopedic, vascular, and prosthetic testimony almost always meet this bar when rooted in clinical literature and peer-reviewed methodology.

- New Jersey (Daubert-like standard post-In re Accutane, 2018): judges serve as gatekeepers of reliability. The expert must base opinions on sufficient data and reliable principles applied to the facts.

To protect admissibility, document every reference your experts rely on—operative reports, photographs, manufacturer data, rehabilitation protocols. Provide clean demonstratives and ensure each visual is clearly marked “for illustrative purposes only.” No speculative imaging, no animations without prior notice. Judges reward transparency.

E. Defense Expert Strategy

Anticipate that the defense will retain its own orthopedist or physiatrist to testify that the plaintiff achieved “excellent functional outcome.” Counter not with hostility, but with surgical facts: show the timeline, the number of operations, and the presence of permanent hardware or prosthetic dependency. Ask defense experts direct questions about permanence:

- “Doctor, can a leg grow back?”

- “Does a prosthesis transmit sensation?”

Those answers end debates faster than argument.

F. The Human Dimension of Expertise

The best experts speak with empathy anchored in science. A calm tone and simple phrasing carry more persuasive weight than outrage. Jurors listen to experts who appear neutral. Encourage witnesses to express facts, not opinions of blame. The jury will fill in the moral verdict themselves.

Trial Hypothetical:

During cross, a defense expert insists that the plaintiff has “adapted beautifully.” On redirect, plaintiff’s prosthetist quietly says, “He has—but adaptation doesn’t mean restoration.” The jurors write it down. One phrase wins the credibility war.

IV. Damages and Recovery

The true measure of a catastrophic leg injury is not found in medical charts—it’s in the erosion of ordinary life. For trial lawyers, the task is to convert that loss into categories the law recognizes without losing its human weight. Proper valuation requires balancing the quantifiable with the existential, ensuring the jury understands both what was spent and what was taken.

A. The Architecture of Damages

In New York and New Jersey, damages in catastrophic injury cases divide into two broad classes: economic and non-economic.

- Economic Damages include medical expenses (past and future), lost earnings, and diminished earning capacity. For an amputee, these extend beyond initial hospitalization to prosthetic replacement, therapy, home modification, and assistive technology. The life-care planner and economist (see Section V) build this framework, using Exhibit L (C-Leg) and Exhibit M (Genium X3) as tangible proof of future medical cost.

- Non-Economic Damages capture pain and suffering, disfigurement, loss of enjoyment of life, and emotional trauma. These require narrative, not spreadsheets. Every exhibit—from the crushed leg in Exhibit A to the prosthetic in Exhibit M—tells a chapter of that story. Together, they define the continuum from injury to endurance.

New York imposes no statutory cap on pain and suffering, nor does New Jersey, though appellate review applies the “shocks the conscience” standard. Within those bounds, the jury’s moral sense determines value. Your role is to give them an honest structure for that moral sense to act upon.

B. Economic Damages: Building the Foundation

Economic recovery begins with hard data. Collect every bill, operative report, and prosthetic invoice. Convert future needs into annualized costs—prosthetic replacement cycles, socket refitting, physical therapy, home adaptations, and transportation modifications. Jurors respect math when it feels precise.

Present the economics sequentially:

- Initial trauma and hospitalization

- Repeated surgeries and infection management

- Amputation and rehabilitation

- Prosthetic fitting, replacements, and maintenance

Use simple visuals: bar charts showing projected lifetime prosthetic cost versus average income. When jurors see a $70,000 prosthesis replaced five times over a working life, they understand the permanence of economic loss.

In New York, past and future medical costs are fully recoverable when properly supported by expert testimony. In New Jersey, lifetime medical care must be shown “with reasonable certainty.” Both jurisdictions permit structured verdicts, but jurors rarely object to lump-sum figures when the necessity is obvious.

C. Non-Economic Damages: Translating Pain Into Law

Pain and suffering resist measurement, yet juries measure them anyway. The task is not to dramatize but to contextualize. A juror will not remember every surgery, but they will remember the sequence: “He fought for a year to save his leg and lost it anyway.” That sentence embodies loss.

Use testimony from the plaintiff and family sparingly. Authentic emotion is powerful; rehearsed grief is not. Let medical witnesses describe pain clinically—nerve damage, phantom sensations, skin breakdown—so the jury understands that suffering is physiological, not performative.

Disfigurement is a separate, visible harm. In New York, “significant disfigurement” exists when a reasonable person would find the alteration distressing or objectionable. The residual limb qualifies categorically. In New Jersey, the same concept falls under significant scarring or disfigurement in AICRA § 39:6A-8(a). Photographs of the healed stump (Exhibit H or K) suffice; no need to expose the client in court unless absolutely necessary.

Loss of enjoyment of life completes the triad. Use small, concrete examples: inability to climb stairs, kneel to play with children, or return to former work. Jurors understand missed moments more than abstract phrases.

Trial Hypothetical:

A 39-year-old warehouse foreman testifies, “I can lift my daughter, but not carry her upstairs.” That line—uttered once—anchors six figures of noneconomic value. Jurors remember the image, not the number.

D. Comparative Fault and Mitigation

Defense counsel may argue that plaintiff conduct contributed to the injury or worsened the outcome through non-compliance. Counter early by showing full medical participation: hospital records, wound-care logs, and physical therapy attendance. In both states, comparative negligence reduces but does not eliminate recovery unless the plaintiff’s fault exceeds 50 percent. Exhibit E (antibiotic beads) and Exhibit F (attempted salvage) visually refute mitigation arguments—the plaintiff did everything possible to preserve the limb.

E. Valuation Ranges and Jury Dynamics

Valuation in amputation cases is less about formula and more about narrative. Nonetheless, historical data guide expectations. Catastrophic leg amputations with prosthetic dependence in New York and New Jersey typically yield total verdicts from $3 million to $12 million, depending on age, occupation, and comparative fault. Multi-surgery cases involving infection and revisions tend toward the higher end, especially with strong visual documentation. Structured settlements may enhance lifetime value while reducing tax exposure.

Never state numbers in opening. Let the evidence build its own gravity. In closing, frame value conceptually: “If a life without pain is worth 100 percent, what does half a life on one leg measure?” Jurors translate that moral math into financial form on their own.

F. The Moral Center of Valuation

Ultimately, valuation is not arithmetic—it’s credibility. Jurors compensate integrity, not sympathy. A plaintiff who admits progress but acknowledges limitations earns trust. A lawyer who argues calmly, not theatrically, earns respect. When both align, verdicts follow.

Leg injury litigation demands discipline: document every surgery, quantify every cost, humanize every consequence. The law does not restore limbs, but it can restore balance. Exhibits A through M are the evidence of that promise—an anatomy of injury turned into a roadmap for justice.

Trial Hypothetical:

A jury in Bergen County awards $8.4 million to a 44-year-old amputee after hearing eight days of testimony. The foreperson later explains: “It wasn’t the pictures. It was that he never exaggerated.” That is the standard you aim for—not sympathy, but belief.

G. The Last Word

When the case closes, jurors should see compensation not as charity but as correction—a recalibration of what negligence took. A right leg represents mobility, dignity, and independence. Once lost, no device can truly replace it. The law’s only remedy is value, measured not in sympathy but in proportion to loss.

Final Note for Counsel:

Always end with hope. The image of the plaintiff standing—prosthesis locked, posture upright—is the visual punctuation to your entire case. It tells the jury: he endured everything you just saw and still stands before you. That is why justice must, and will, stand with him.

About Gersowitz Libo & Korek, P.C.

Founded in 1984 by Andrew L. Libo and Edward H. Gersowitz—later joined by Jeff S. Korek—Gersowitz Libo & Korek, P.C. has represented injury victims throughout New York and New Jersey for over forty years. The firm has recovered more than $1 billion for clients and is consistently recognized by Best Law Firms and Best Lawyers in America.

With offices in Manhattan, Englewood, and East Hampton, GLK focuses on personal injury, medical malpractice, construction accidents, premises liability, and product-liability litigation. The firm’s success stems from preparation, courtroom skill, and the conviction that serious injuries deserve serious advocacy.